From Corporate Church to Missional Church: The Challenge Facing Congregations Today - Craig Van Gelder

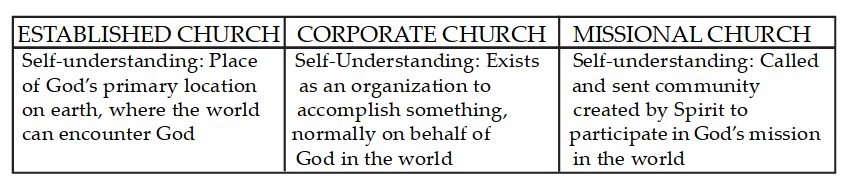

Previous post : Lecture : Panchuck (& Hareth) All Things Work Together for Good: Theodicy as GaslightingVan Gelder contrasts what he calls Corporate and Missional church self-understandings. He contextualizes the appearance of what he calls the Corporate Church model as an American development growing from the unique, religiously plural context of the early USA, as distinct from a European “Established Church” (state church/Constantinian) model. He then walks through five stages of its development, and then argues how a Missional Church self-understanding is more theologically and biblically appropriate. Of the three paradigms, the Established and Missional paradigms both build their primary self-understanding on God’s working, though they understand the location of his work differently: established churches see the Church as “the primary horizon of God’s activity in the world” (426) ; the missional church sees the world as the primary place of God’s work, and the role of the Church is to participate in this work (this is the theology of the missio dei or “mission of God”, an academic consensus view which flows from the major theological & ecclesiological developments of the 20th century). The self-understanding of the Corporate church, however,is built on an Modern-era, industrial, organizational paradigm whose self-understanding is primarily a question of a task: the church exists, like other organizations, to accomplish something. (Note: Van Gelder doesn’t seem to notice he’s speaking ideal-typically here; these are doubtless never pure realities).

(p. 426)

(p. 426)

The first step in appearance of the Organizational Church model came about because the USA has never had an Established (state) church, and so a different model had to take hold. “By the mid-to-late 1700s, [the Corporate] self-understanding became the normative understanding of the newly forming denominations and their congregations in the colonies” (427); without the legitimacy of being “the Established (understood as established, institutionally, by God) Church”, this model was built from a combination of other social forms, some of which were unique to the colonial experience. The main forms were a free church ecclesiology (a Radical Reformation/anabaptist development) and the idea of voluntary associations. This latter social form grew out of the need for the colonies to build an entirely new social order (430) into which they could import some, but not all, European forms. In place of a society where belonging and participation were largely determined by default, like family, neighbourhood, parish, etc. the voluntary association is a group that is chosen, often for some practical purpose. Alexis de Tocqueville, (the famous French proto-sociologist who wrote extensively on American social and political realities after visiting the USA in the 1830s) would call the voluntary association “one of the more unique features of the emerging American society”. This colonial experience (1600s-1780s) represents the first of five stages of the developing Organizational model. (Note: I suspect a link here with poor returns in church planting in European territories; if a church model is based on a social form that doesn’t exist in these places, it will be very difficult to implant).

The second stage, Van Gelder calls The Purposive Denomination (1790-1870; dates are of course approximate). This denominational climate was a “unique creation within the American setting (431)” and a major change from the previous 1400 years of ecclesiology. Early in this period, denominations had developped three-level structures, “a national assembly, regional judicators, and local congregations,” which followed a functionalist organizational identity – “it must do something in order to justify its existence.” This functional purpose was largely shaped by frontier revivals and the second great awakening, leading to the development of methods to accomplish the organizational mission. It was in the second half of the 19th century that “the modern organizational, denominational church had become the norm for church life in the United States.” (433) The third phase, The Churchly Denomination (1870-1920) followed the rationalization, professionalization and bureaucratization of the Modern period, for example with highly seminary trained clergy.

Between the 1920s and the 70s, a period which Van Gelder calls The Corporate Denomination, the Taylorist schools of “Scientific Management” gained steam in the churches, focusing on productivity, efficiency and business organization. This brought the appearance of the locally- and socially-disembedded, suburban, commuter church, modeled as “something of a business establishment” (Shailer Matthews, 1912), where “corporate identity came to be established primarily around shared programmatic activities” (435). According to Van Gelder this model collapsed after the 1970s (Note: Really?!). The move to The Regulatory Denomination (1970 forward) marks a market-driven, social-science backed, pragmatic and technique-based efforts to revitalize these existing structures. He is very critical of this perspective, as the following citation shows: « At the heart of these various marketdriven and/or mission-driven models is a theology of the great commission, where mission is understood primarily as something the church must do, which reinforces a functional view of the corporate church within its organizational self understanding. » (p. 437)

The remainder of the article gives a pretty good summary of the biblical and theological basis for a Missional self-understanding of the church, building on the now consensus views of Trinitarian eccleisology, The Kingdom of God as the comprehensive reconciliation and restoration of all things in Christ, and the missio dei as God’s work to do that as seen in the Covenants, Jesus’ Kingdom preaching, and the praxis of the book of Acts. These are valuable, but not really the newness of this article.